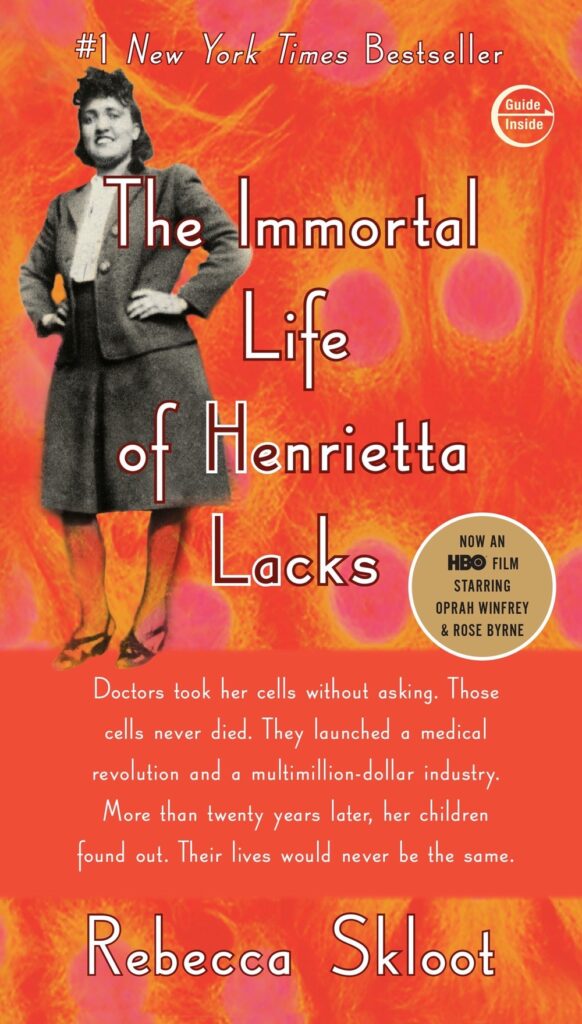

Sharing my learnings from the book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks tells a riveting story of the collision between ethics, race, and medicine; of scientific discovery and faith healing; and of a daughter consumed with questions about the mother she never knew. It’s a story inextricably connected to the dark history of experimentation on African Americans, the birth of bioethics, and the legal battles over whether we control the stuff we’re made of.

- author Rebecca Skloot details the history of the cells which outlived Henrietta Lacks, along with the rise and establishment of the cell-culture & gene-patenting industry

- on august 1, 1920, in Roanoke Virginia, a girl who would change medical science forever was born. Her name was Henrietta.

- she was a poor tobacco farmer. Married her cousin at an age of 29 and has children.

- in early 1951, Henrietta walked into the designated coloreds-only examination room of John Hopkins gynecology center. She’d discovered a lump on her cervix. Doctors took a sample & rushed it to the pathology lab for diagnosis. Her biopsy result was that Henrietta had epidermis carcinoma of the cervix, stage I. At the time, John Hopkins were using radium – a radioactive material – to treat cervical cancer. Henrietta gave her official consent for any treatments or survey the doctors deemed necessary. While the treatments were intensive, they were ultimately ineffective. Henrietta Lacks died a October 4, 1951.

- in the early 1950s, scientists and doctors were searching for way to keep human cells alive outside the body so that they could conduct experimental research that would contribute to curing illnesses. As luck would have it, John Hopkins’ head of tissue culture research, George Gey, was also an inventor and visionary. Get came up with the roller-tube culturing technique. This involved a cylinder, punched with holes to accommodate special test tubes, rotating very slowly, 24 hours a day

- Gey’s technique was used on Henrietta’s isolated cancel cells labeled “HeLa”. Gey’s assistant (Kubicek) and other researchers were shocked that 2 days later, the cells were still alive and doubling every 24 hours! It wasn’t only the technique but the cells’ aggressive nature. Gey proudly announced he’d grown “the first immortal cells” and soon began sharing them with labs that wanted to use the cells in research on illnesses such as polio and cancer

- to help combat diseases like polio and cancer, scientists created a factory for producing HeLa cells

- cost of producing the cells and performing research on them was relatively low

- most studies aiming to find cures for diseases used monkeys as test subjects. But experimenting on monkeys was expensive

- HeLa cells were able to survive in a culture medium

- HeLa cells were particularly resilient to being transported across the country

- HeLa cells are highly susceptible to the polio virus

- the National foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFIP) setup the HeLa distribution center to facilitate the growth and distribution of the HeLa cells for research lab

- although her cells spread across the globe, Henrietta and her family were largely forgotten. After Henrietta’s death, her family struggled to survive

- The family reluctancy and suspicion with the medical profession had its roots in a major distrust of and apprehension toward the medical field, because of its history with black Americans

- although HeLa cells helped many scientific discoveries, their prevalence threatened much research.

- geneticist Stanley Gartler had been conducting research with the aim of finding new genetic markers. At a 1965 cell culture conference, Gartler revealed that he discovered that the most commonly used cultures in cell research all had one marker in common. In other words, the HeLa cells had contaminated all the cultures they’d been near. While the majority of doctors continued working on the cultures, a few took Gartler seriously. Those doctors needed to find a way to identify the presence of HeLa, a need that led them to Henrietta’s family

- the doctors hoped that by taking samples from the family, they would be able to continue research on the contamination, and develop a way to map the human genome. That’s how the doctors and the Lacks family came together to discuss Henrietta

- The HeLa case is not the only one that involved concerns about privacy in cell donation

- Alaskan pipeline worker, John Moore. Cancer researcher David Golde at UCLA treated Moore, removing his bulging spleen. While Moore continued his treatment, Golde developed & marketed Moore’s cells without informing him. Once Moore discovered what had been going on. He sued Golde for both breach of privacy & profiting from his own cells without obtaining consent

- Ted Slavin was born a hemophiliac. As a result, his body had already been producing antibodies for hepatitis B. Slavin’s doctor informed Ted that he could market his cell line and make a lot of money.

- what distinguished both Moore and Slavin from Henrietta was the fact that they were both able to contest the use of their cells.

- if doctors want to take samples for research, they require the consent of the patient. However, they do not require consent if they wish to store samples from diagnostic procedures for future research

- In 1999, President Clinton’s National Bioethics Advisory Commission issued a report stating that federal oversight of tissue research was lacking. And, though they advised that patients should be granted more rights regarding what their cells were used for, they remained quiet about the financial issue and who should profit

Leave a Reply