Sharing my learnings from the book, Black Spartacus by Sudhir Hazareesingh

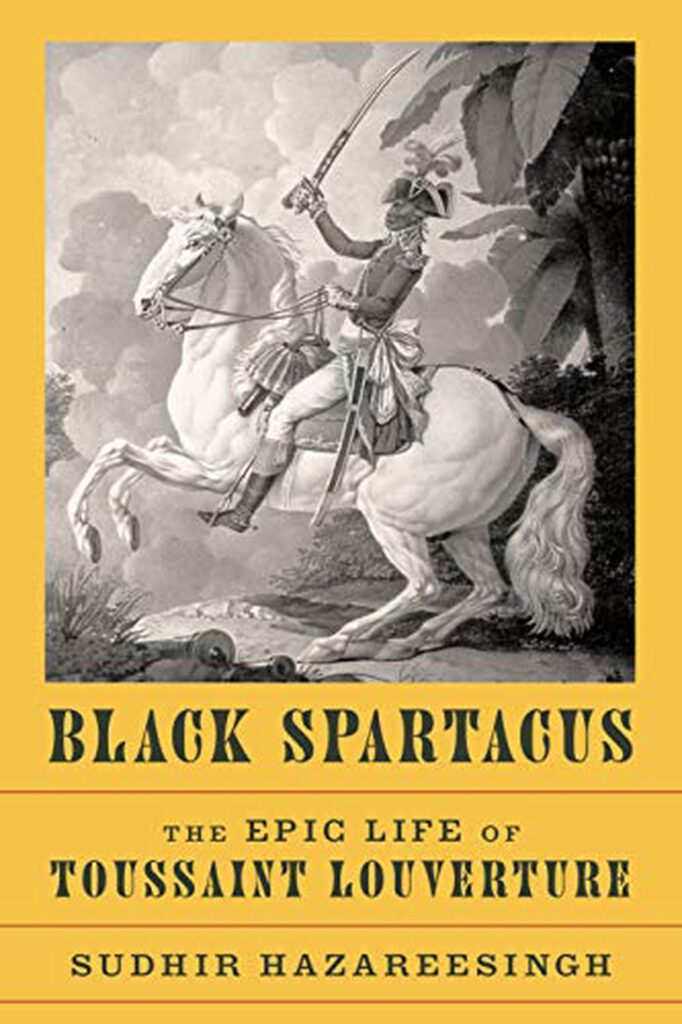

Black Spartacus by Sudhir Hazareesingh

Toussaint Louverture is the most enigmatic. Though the Haitian revolutionary’s image has multiplied across the globe―appearing on banknotes and in bronze, on T-shirts and in film―the only definitive portrait executed in his lifetime has been lost. Well versed in the work of everyone from Machiavelli to Rousseau, he was nonetheless dismissed by Thomas Jefferson as a “cannibal.” A Caribbean acolyte of the European Enlightenment, Toussaint nurtured a class of black Catholic clergymen who became one of the pillars of his rule, while his supporters also believed he communicated with vodou spirits. And for a leader who once summed up his modus operandi with the phrase “Say little but do as much as possible,” he was a prolific and indefatigable correspondent, famous for exhausting the five secretaries he maintained, simultaneously, at the height of his power in the 1790s. Employing groundbreaking archival research and a keen interpretive lens, Sudhir Hazareesingh restores Toussaint to his full complexity in Black Spartacus. At a time when his subject has, variously, been reduced to little more than a one-dimensional icon of liberation or criticized for his personal failings―his white mistresses, his early ownership of slaves, his authoritarianism ―Hazareesingh proposes a new conception of Toussaint’s understanding of himself and his role in the Atlantic world of the late eighteenth century. Black Spartacus is a work of both biography and intellectual history, rich with insights into Toussaint’s fundamental hybridity―his ability to unite European, African, and Caribbean traditions in the service of his revolutionary aims. Hazareesingh offers a new and resonant interpretation of Toussaint’s racial politics, showing how he used Enlightenment ideas to argue for the equal dignity of all human beings while simultaneously insisting on his own world-historical importance and the universal pertinence of blackness―a message which chimed particularly powerfully among African Americans. Ultimately, Black Spartacus offers a vigorous argument in favor of “getting back to Toussaint”―a call to take Haiti’s founding father seriously on his own terms, and to honor his role in shaping the postcolonial world to come.

- the story of Toussaint Louverture, the Black Spartacus – A man born into slavery, who rose up and helped lead the first ever successful revolt of enslaved people

- Toussaint began his life on a sugar plantation owned by a French marine officer named Count Pantaléon de Bréda. As a child, he was so weak and sickly that he received the nickname “Fatras-Bâton,” which in the local creole dialect meant “skinny stick.”

- However, Toussaint didn’t remain Fatras-Bâton for long. Through sheer determination, the fragile boy grew into a strong young man. Even as a young man, Toussaint had a bold personality and a deep sense of confidence in his abilities and worth.

- Toussaint’s resolute personality was partially forged by his strong Catholic faith. Some scholars suggest that the young man even began training to be a priest in the Jesuit order. Alongside this Catholic influence was Toussaint’s connection to his African heritage.

- Toussaint also forged a strong working relationship with Antoine-François Bayon de Libertat.

- Toussaint served as his right-hand man. He helped the colon with everything from driving his coach to accompanying him on business trips throughout the colony. This was a prestigious role for a slave, and it helped Toussaint acquire a bit of wealth and respect. In fact, Bayon was so impressed with Toussaint’s work that, in 1776, he helped free him.

- Even as a freeman, there were few opportunities for him on the island and all of his extended family remained enslaved on the estate. So, Tousaint stayed at Bréda.

- By the early 1790s, Toussaint was about fifty and still living on the Bréda sugar plantation. But huge change was on the horizon. In Europe, the French revolution was in full swing. In 1789 the revolutionaries signed the Declaration of the Rights of Man, granting popular sovereignty and civil rights to men.

- Back on Saint-Domingue, there was heated debate on whether the Declaration would include rights for the island’s mixed-race and Black population. In the end, a more conservative faction of white landowners won out. Any talk of granting rights to non-whites or freeing enslaved people was banned.

- But, the idea of liberty could not be suppressed. In August of 1791, tensions on Saint-Domingue finally boiled over. A militia of thousands of Black and mixed-race residents stormed plantations in the north of the island. The revolution grew in power, but French forces fought back. Beginning in October 1792, the tide began to turn in favor of the French. That winter, a bevvy of reinforcements from Europe launched a heavy counter-offense that forced the rebels back on their heels.

- So, in the first months of 1793, the rebel leadership turned to the Spanish for help. Toussaint – who’d now become a leading figure in the rebellion – was dispatched to the neighboring colony of Santo Domingo to negotiate an agreement. He returned triumphant. The Spanish agreed to provide military aid to the rebellion.

- Yet, his newfound commitment to universal freedom caused friction. His colleagues, Jean-François and Georges Biassou, were wavering on the issue of emancipation. Moreover, the more conservative-leaning factions of the Spanish forces were reluctant to follow through on their pledge to take in Black people as citizens. And, finally, as if all this wasn’t enough, Britain entered the fray, in a vain attempt to capture the colony for its own purposes.

- Faced with this disarray, Toussaint made a bold decision. He contacted Étienne Maynaud de Laveaux, the new French governor of Saint-Domingue. The French republicans were now, more than ever, ready to emancipate slaves in the colonies. So, in May 1794, Toussaint cut ties with the Spanish and joined forces with his former enemies, the French.

- At the beginning of 1795, Laveaux and his French republicans weren’t in a particularly strong position. Yet, Toussaint rose to the challenge. In the next few years, he completely dedicated himself to the war effort.

- By late 1798, Toussaint’s heroic efforts had paid off. As the commander-in-chief of Saint-Domingue’s army, he had successfully defeated both the Spanish and the British. As a new century dawned, the area was back in French republican control and Toussaint stood as one of the most powerful figures on the island.

- After years of rebellion and war, Saint-Domingue was in crisis. The colony’s infrastructure was in terrible shape. In order to rebuild the island, and protect his own power, Toussaint began forging diplomatic ties with a new emerging power: The United States. the US agreed to buy much of the colony’s sugar, coffee, and other commodities. The economic partnership was a boon for Saint-Domingue and a much-needed win for Toussaint as a statesman.

- While Toussaint had successfully remade Saint-Domingue into a more egalitarian society, he did not feel his revolutionary work was done. The French colony only occupied one half of the island of Hispaniola, while the eastern half of the island was still under Spanish control. However, the French did not share his revolutionary zeal. Napoleon, who had recently seized power in France, was reluctant to start a war with Spain.

- In the winter of 1800, Toussaint gathered a force of 10,000 men and marched on the eastern half of the island. The Spanish put up surprisingly little resistance. In a matter of weeks, Toussaint was victorious.

- Toussaint’s unification of Hispaniola ushered in an era of rapid change on the island. Shortly after his victory at Santiago, Toussaint organized a General Assembly to ratify a new constitution for the colony.

- However, the celebrations would not last long. The European powers had become wary of Toussaint’s massive popularity and hostile to the idea of an entire free, Black republic in the Caribbean. And so in a few months, the colony would once again be thrust into conflict.

- in October of 1801, Napoleon dispatched an invasion force to the Caribbean. It was led by a general named Victoire-Emmanuel Leclerc, and his instructions were simple: depose Toussaint and reinstate slavery on the island.

- But, Toussaint was ready. For months he had imported huge stores of weapons from America and hid them in secret stashes across the island. Over the course of 70 days, Toussaint’s forces slowly wore down the French invaders. By March 1802, they even managed to retake several key cities. Toussaint, ever the pragmatic leader, reached out to Leclerc in order to negotiate a truce. After all, despite the conflict, Toussaint and his men still held loyalty to France. The two men settled on a deal. The fighting would cease and the two commanders would work out a peaceful way forward.

- Unfortunately, Toussaint would not see any peaceful future. In June 1802, he was invited to a dinner by the French general Jean-Baptiste Brunet. Shortly after Toussaint arrived at Brunet’s estate, a contingent of Leclerc’s men seized the commander and placed him under arrest on charges of sedition. It was a grim existence but Toussaint faced it with steady resolve. In a series of letters to Napoleon, the captured leader reaffirmed his commitment to the republican ideals of liberty and freedom.

- Eventually, the cold weather and dire conditions of Fort de Joux became too much for the aging revolutionary. In the winter of 1803, he developed a strong cough and rapidly lost weight. On the morning of April 7, Toussaint was found dead in his cell. He was quickly and quietly buried at the fort’s chapel.

- But, while Toussaint himself had died, the struggle he had led continued. Back on Saint-Domingue, the French forces were losing control. The local population – incensed about Toussaints capture and wary of new rumors that slavery would be reinstated – was in open revolt. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of Toussaint’s comrades and confidants, seized the moment. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared independence from France. From that moment on, Saint-Domingue would no longer be a colony, but it’s own country, Haiti.

- The Haitian Revolution, and the legacy of Black liberation it represents, owes a huge debt to Toussaint’s leadership. His vision of a society based on equality and self-determination helped guide the colony from its dark beginnings as a slave-state to the first Black democracy in the new world.

Leave a Reply